For example, as we watch Kane's mother sign the papers that will make an East Coast banker his guardian, through a window in the background we can see the boy Kane playing in the snow, perhaps his last experience of real happiness.

As film buffs know, Welles fully exploited the technique in his 1941 Citizen Kane, where he frequently uses it to show Kane's isolation from other characters. Neither director seems to have influenced the other in doing this: though Welles's Macbeth was released in December 1948, seven months after Olivier's Hamlet, it had been shot and edited the previous year.īoth films take advantage of deep focus, a technique in which the foreground and background of a shot are in clear focus. But Olivier and Orson Welles were the first to use these techniques in a Shakespeare movie. German Expressionist and film noir directors did this as well. Olivier wasn't the first director to use camera movements and dissolves to reflect his protagonist's thoughts. Before we hear these lines, Olivier provides us with a visual representation of them, his lap dissolve from the rumpled sheets to Claudius's face. At the soliloquy's climax, we learn that his revulsion rises from the thought of Gertrude having sex with Claudius: "O, most wicked speed, to post / With such dexterity to incestuous sheets!" (1.2.156-57). Hamlet begins the soliloquy with a death wish and then moves to the source of that wish-his disgust at his mother's remarriage. The wild camera movements and final dissolve foreshadow Hamlet's story and his first soliloquy, which Olivier delivers from the chair we have just seen. We move through the window into the royal bedroom, coming close to the bed's rumpled sheets before the shot dissolves into one of Claudius drinking, the beginning of the second scene. For a moment, we hear the sweet melody that will accompany her scenes, and then the music intensifies as we swoop up toward a window. It then turns and moves toward the hall leading to Ophelia's room. The camera turns around and around until we see the empty court, at which point the camera dives down and hovers over Hamlet's empty chair.

Olivier swings the away from these characters and spirals it down through the tower's interior. We end the first scene on the castle tower, with Horatio and the soldiers agreeing to tell Hamlet about the Ghost. The film's transition from what would be the play's first to its second scene provides a good example.

That creativity shows itself in Olivier's use of swooping camera movements and lap dissolves to reflect Hamlet's predicament and thoughts. This was their second surprise: they had thought of Olivier primarily as an actor and didn't know that he was also a tremendously creative director. Though it took a while for my students to appreciate the acting in Olivier's Hamlet, they were immediately impressed by its cinematography. For the uninitiated, the acting in Olivier's Shakespeare films takes some getting used to, but, as is true of so many things, newbies who give it a chance may discover a new pleasure. If I had started the class by playing those performances back to back, the students would probably have ranked Olivier and Simmons a distant third. Some students who had seen Mel Gibson and Helena Bonham Carter and/or Kenneth Branagh and Kate Winslet in the same scene thought that Olivier and Simmons's performance was better. A few students still thought that the acting, especially that of Jean Simmons as Ophelia, was overly theatrical, but they all admired the subtlety of Olivier's performance, how, for example, in the "nunnery" scene, his facial expressions tell us that Hamlet finds what he's doing painful. I stopped the movie at this point-embarrassing some students with tear-stained faces-and we discussed what we had seen.

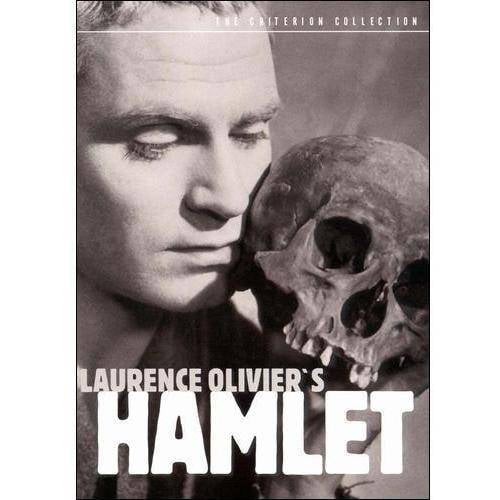

When I recently showed Laurence Olivier's 1948 Hamlet to a class of college students, two things surprised them.įirst, because of what they had had heard about Olivier, they had expected great acting, but they initially found the performances hammy, like "old-fashioned stage acting." After a while, they became used to this more theatrical style, and by the time we reached Hamlet's "get thee to a nunnery" confrontation with Ophelia, most were too caught up in the story to think about the performances.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)